The Destabilization of Pakistan By Prof. Michel Chossudovsky | |

Global Research, December 30, 2007 | |

The assassination of Benazir Bhutto has created conditions which contribute to the ongoing destabilization and fragmentation of Pakistan as a Nation. The process of US sponsored "regime change", which normally consists in the re-formation of a fresh proxy government under new leaders has been broken. Discredited in the eyes of Pakistani public opinion, General Pervez Musharaf cannot remain in the seat of political power. But at the same time, the fake elections supported by the "international community" scheduled for January 2008, even if they were to be carried out, would not be accepted as legitimate, thereby creating a political impasse. There are indications that the assassination of Benazir Bhutto was anticipated by US officials:

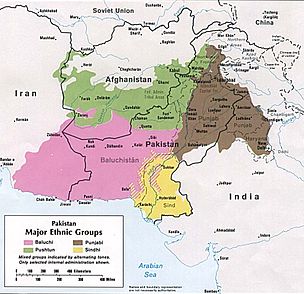

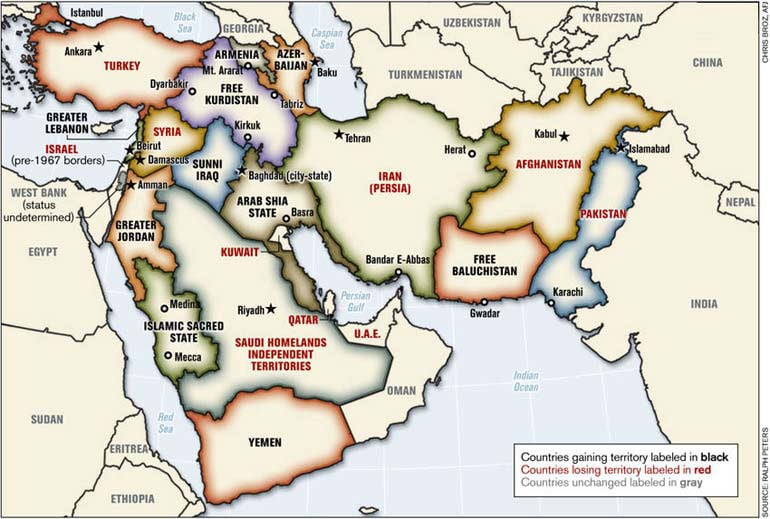

Political Impasse "Regime change" with a view to ensuring continuity under military rule is no longer the main thrust of US foreign policy. The regime of Pervez Musharraf cannot prevail. Washington's foreign policy course is to actively promote the political fragmentation and balkanization of Pakistan as a nation. A new political leadership is anticipated but in all likelihood it will take on a very different shape, in relation to previous US sponsored regimes. One can expect that Washington will push for a compliant political leadership, with no commitment to the national interest, a leadership which will serve US imperial interests, while concurrently contributing under the disguise of "decentralization", to the weakening of the central government and the fracture of Pakistan's fragile federal structure. The political impasse is deliberate. It is part of an evolving US foreign policy agenda, which favors disruption and disarray in the structures of the Pakistani State. Indirect rule by the Pakistani military and intelligence apparatus is to be replaced by more direct forms of US interference, including an expanded US military presence inside Pakistan. Asia geopolitical situation and Washington's ongoing plans to extend the Middle East war to a much broader area. The US has several military bases in Pakistan. It controls the country's air space. According to a recent report: "U.S. Special Forces are expected to vastly expand their presence in Pakistan, as part of an effort to train and support indigenous counter-insurgency forces and clandestine counterterrorism units" (William Arkin, Washington Post, December 2007). The official justification and pretext for an increased military presence in Pakistan is to extend the "war on terrorism". Concurrently, to justify its counterrorism program, Washington is also beefing up its covert support to the "terrorists." The Balkanization of Pakistan Already in 2005, a report by the US National Intelligence Council and the CIA forecast a "Yugoslav-like fate" for Pakistan "in a decade with the country riven by civil war, bloodshed and inter-provincial rivalries, as seen recently in Balochistan." (Energy Compass, 2 March 2005). According to the NIC-CIA, Pakistan is slated to become a "failed state" by 2015, "as it would be affected by civil war, complete Talibanisation and struggle for control of its nuclear weapons". (Quoted by former Pakistan High Commissioner to UK, Wajid Shamsul Hasan, Times of India, 13 February 2005): Continuity, characterized by the dominant role of the Pakistani military and intelligence has been scrapped in favor of political breakup and balkanization. According to the NIC-CIA scenario, which Washington intends to carry out: "Pakistan will not recover easily from decades of political and economic mismanagement, divisive policies, lawlessness, corruption and ethnic friction," (Ibid) . The US course consists in fomenting social, ethnic and factional divisions and political fragmentation, including the territorial breakup of Pakistan. This course of action is also dictated by US war plans in relation to both Afghanistan and Iran. This US agenda for Pakistan is similar to that applied throughout the broader Middle East Central Asian region. US strategy, supported by covert intelligence operations, consists in triggering ethnic and religious strife, abetting and financing secessionist movements while also weakening the institutions of the central government. The broader objective is to fracture the Nation State and redraw the borders of Iraq, Iran, Syria, Afghanistan and Pakistan. Pakistan's Oil and Gas reserves as well as its pipeline corridors are considered strategic by the Anglo-American alliance, requiring the concurrent militarization of Pakistani territory. Balochistan comprises more than 40 percent of Pakistan's land mass, possesses important reserves of oil and natural gas as well as extensive mineral resources. The Iran-India pipeline corridor is slated to transit through Balochistan. Balochistan also possesses a deap sea port largely financed by China located at Gwadar, on the Arabian Sea, not far from the Straits of Hormuz where 30 % of the world's daily oil supply moves by ship or pipeline. (Asia News.it, 29 December 2007) Pakistan has an estimated 25.1 trillion cubic feet (Tcf) of proven gas reserves of which 19 trillion are located in Balochistan. Among foreign oil and gas contractors in Balochistan are BP, Italy's ENI, Austria's OMV, and Australia's BHP. It is worth noting that Pakistan's State oil and gas companies, including PPL which has the largest stake in the Sui oil fields of Balochistan are up for privatization under IMF-World Bank supervision. According to the Oil and Gas Journal (OGJ), Pakistan had proven oil reserves of 300 million barrels, most of which are located in Balochistan. Other estimates place Balochistan oil reserves at an estimated six trillion barrels of oil reserves both on-shore and off-shore (Environment News Service, 27 October 2006) . Covert Support to Balochistan Separatists agenda. Following a familiar pattern, there are indications that the Baloch insurgency is being supported and abetted by Britain and the US. 1940s, when Balochistan was invaded by Pakistan. In the current geopolitical context, the separatist movement is in the process of being hijacked by foreign powers. British intelligence is allegedly providing covert support to Balochistan separatists (which from the outset have been repressed by Pakistan's military). In June 2006, Pakistan's Senate Committee on Defence accused British intelligence of "abetting the insurgency in the province bordering Iran" [Balochistan]..(Press Trust of India, 9 August 2006). Ten British MPs were involved in a closed door session of the Senate Committe on Defence regarding the alleged support of Britain's Secret Service to Balcoh separatists (Ibid). providing American F-16 jets to Pakistan, which are being used to bomb Baloch villages in Balochistan. Meanwhile, British alleged covert support (according to the Pakistani by Senate Committee) contributes to weakening the central government. as well as as training to "Liberation Armies" ultimately with a view to destabilizing sovereign governments. In Kosovo, the training of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) in the 1990s had been entrusted to a private mercenary company, Military Professional Resources Inc (MPRI), on contract to the Pentagon. by the drug trade and supported by the CIA and Germany's Bundes Nachrichten Dienst (BND). tangible links to the Baloch resistance movement, which developed since the late 1940s. An aura of mystery surrounds the leadership of the BLA. Baloch population in Pink: In Iran, Pakistan and Southern Afghanistan Washington favors the creation of a "Greater Balochistan" which would integrate the Baloch areas of Pakistan with those of Iran and possibly the Southern tip of Afghanistan (See Map above), thereby leading to a process of political fracturing in both Iran and Pakistan.

Military scholar Lieutenant Colonel Ralph Peters writing in the June 2006 issue of The Armed Forces Journal, suggests, in no uncertain terms that Pakistan should be broken up, leading to the formation of a separate country: "Greater Balochistan" or "Free Balochistan" (see Map below). The latter would incorporate the Pakistani and Iranian Baloch provinces into a single political entity. In turn, according to Peters, Pakistan's North West Frontier Province (NWFP) should be incorporated into Afghanistan "because of its linguistic and ethnic affinity". Although the map does not officially reflect Pentagon doctrine, it has been used in a training program at NATO's Defense College for senior military officers. This map, as well as other similar maps, have most probably been used at the National War Academy as well as in military planning circles. (See Mahdi D. Nazemroaya, Global Research, 18 November 2006) "Lieutenant-Colonel Peters was last posted, before he retired to the Office of the Deputy Chief of Staff for Intelligence, within the U.S. Defence Department, and has been one of the Pentagon’s foremost authors with numerous essays on strategy for military journals and U.S. foreign policy." (Ibid)

There are separatist groups in Sindh province, which are largely based on opposition to the Punjabi-dominated military regime of General Pervez Musharraf (For Further details see Selig Harrisson, Le Monde diplomatique, October 2006) "Strong Economic Medicine": Weakening Pakistan's Central Government Pakistan has a federal structure based on federal provincial transfers. Under a federal fiscal structure, the central government transfers financial resources to the provinces, with a view to supporting provincial based programs. When these transfers are frozen as occurred in Yugoslavia in January 1990, on orders of the IMF, the federal fiscal structure collapses:

It is by no means accidental that the 2005 National Intelligence Council- CIA report had predicted a "Yugoslav-like fate" for Pakistan pointing to the impacts of "economic mismanagement" as one of the causes of political break-up and balkanization. international financial institutions to describe the chaos which results from not fully abiding by the IMF's Structural Adjustment Program. In actual fact, the "economic mismanagement" and chaos is the outcome of IMF-World Bank prescriptions, which invariably trigger hyperinflation and precipitate indebted countries into extreme poverty. Pakistan has been subjected to the same deadly IMF "economic medicine" as Yugoslavia: In 1999, in the immediate wake of the coup d'Etat which brought General Pervez Musharaf to the helm of the military government, an IMF economic package, which included currency devaluation and drastic austerity measures, was imposed on Pakistan. Pakistan's external debt is of the order of US$40 billion. The IMF's "debt reduction" under the package was conditional upon the sell-off to foreign capital of the most profitable State owned enterprises (including the oil and gas facilities in Balochistan) at rockbottom prices . Musharaf's Finance Minister was chosen by Wall Street, which is not an unusual practice. The military rulers appointed at Wall Street's behest, a vice-president of Citigroup, Shaukat Aziz, who at the time was head of CitiGroup's Global Private Banking. (See WSWS.org, 30 October 1999). CitiGroup is among the largest commercial foreign banking institutions in Pakistan. There are obvious similarities in the nature of US covert intelligence operations applied in country after country in different parts of the so-called "developing World". These covert operation, including the organisation of military coups, are often synchronized with the imposition of IMF-World Bank macro-economic reforms. In this regard, Yugoslavia's federal fiscal structure collapsed in 1990 leading to mass poverty and heightened ethnic and social divisions. The US and NATO sponsored "civil war" launched in mid-1991 consisted in coveting Islamic groups as well as channeling covert support to separatist paramilitary armies in Bosnia, Kosovo and Macedonia. the National Intelligence Council and the CIA: From the point of view of US intelligence, which has a longstanding experience in abetting separatist "liberation armies", "Greater Albania" is to Kosovo what "Greater Balochistan" is to Pakistan's Southeastern Balochistan province. Similarly, the KLA is Washington's chosen model, to be replicated in Balochistan province. The Assassination of Benazir Bhutto Benazir Bhutto was assassinated in Rawalpindi, no ordinary city. Rawalpindi is a military city host to the headquarters of the Pakistani Armed Forces and Military Intelligence (ISI). Ironically Bhutto was assassinated in an urban area tightly controlled and guarded by the military police and the country's elite forces. Rawalpindi is swarming with ISI intelligence officials, which invariably infiltrate political rallies. Her assassination was not a haphazard event. Without evidence, quoting Pakistan government sources, the Western media in chorus has highlighted the role of Al-Qaeda, while also focusing on the the possible involvement of the ISI. What these interpretations do not mention is that the ISI continues to play a key role in overseeing Al Qaeda on behalf of US intelligence. The press reports fail to mention two important and well documented facts:

The involvement of either Al Qaeda and/or the ISI would suggest that US intelligence was cognizant and/or implicated in the assassination plot. | |

Monday, December 31, 2007

The Destabilization of Pakistan

Friday, November 30, 2007

FOOTLOOSE: On Raja Paurava and Alexander — Salman Rashid

I lament that we in Pakistan, those of us whose ancestors converted to Islam, insist on denying our pre-conversion history. For us, it simply does not exist. We invent tales of imaginary ancestors having arrived in the subcontinent duly converted to the ‘one and only true faith’ from some place in Iran or Central Asia. Pride of place of course goes to all those who subscribe to the yarn of their ancestors’ heroic overland trek direct from Mecca. I know of families who possess genealogical charts connecting them to prophets of yore and, in one case, even to Adam himself!

Consequently, everything that transpired in this great and wonderful land of the Sindhu River before the arrival of these august (albeit imaginary) personalities was Kafir. To be proud of it is criminal; to acknowledge it negligent of religious duty. Not surprising then that some of us even have a problem mentioning Moen jo Daro and Harappa.

Since all our imaginary Islamic ancestors came from the west, we somehow got it into our heads that all those who came from that direction were also necessarily Muslims. An ‘historian’ at Taxila once told me that Alexander the Macedonian was one of Islam’s greatest heroes. Similarly, on a visit to the village of Mong (Mandi Bahauddin) many years ago, a man floored me by not only commending Alexander as a personality of the Scripture but also for reviling Paurava (Porus in Greek) as a Hindu. But history remembers Raja Paurava as a man of rare character.

The Battle of the Hydaspes (Jhelum River) was fought in the year 326 BCE on a beautiful morning in late May after a night of torrential rain. The crystalline blue sky would have been piled up with cumulus when Paurava’s Punjabis advanced to meet their foe the Macedonian, Greek, Scythian, Persian and even a brigade of Punjabi troops from Taxila. From even before day broke, it was a hard fought contest. And before the sun had started to wester, the Punjabis were in disarray. The battle had been lost.

Arrian, the Greek historian, writing four hundred years after this epic battle pays tribute to Raja Paurava thus — and there can be no greater tribute for it comes from a foreigner: ‘Throughout the action Porus proved himself a man indeed, not only as a commander but as a solider of the truest courage...his behaviour was very different from that of the Persian King Darius: unlike Darius, he did not lead the scramble to save his own skin ... [but] fought bravely on.’

With all his units dispersed, Paurava, himself grievously wounded in the right shoulder, eventually submitted to an old philosopher friend of his and permitted himself to be led into Alexander’s presence. Arrian recalls that encounter: ‘[Alexander] looked at his adversary with admiration: he was a magnificent figure of a man, five cubits high and of great personal beauty.’ The cubit being variable in various parts of Greece, this figure would yet mean that Paurava was no less than seven feet tall! And Alexander of middling stature would have had to look up into those dark eyes and the sweat-streaked face.

It was then that the famous exchange took place that even the most ignorant among us know of. What, asked Alexander, would Paurava wish that the conqueror do with him and Paurava replied that he wished to be treated as a king. This much we all know. But Alexander had a farther query. ‘For my part your request shall be granted. But is there not something you would wish for yourself? Ask it.’ And Paurava the Punjabi who we are ashamed to claim as our own said that everything was contained in this one request.

Peace was made between the victor and the vanquished and it has been said that this was one battle where both sides emerged victorious. Alexander returned Paurava’s kingdom to him and shortly after the death of the king of Taxila asked Paurava to look after the affairs of that kingdom as well. Just three years after this great battle on the Jhelum, Alexander died under mysterious circumstances in Babylon. That was June 323 BCE. Within years, the great Raja Paurava was assassinated and the story seems to have ended. But not quite.

In 44 CE, Taxila was visited by a Greek philosopher named Apollonius. The philosopher’s account (kept by his diarist) tells us of two temples, one outside the city walls and the other by the main street leading to the king’s palace. Both temples had large copper plate murals adorning their walls. The murals depicted scenes of battle from the struggle that had taken place on the banks of the Jhelum River three hundred and sixty-seven years earlier.

The account marvels at the finesse of the renditions: the colours and the forms were as though one were watching a real scene frozen in time. The murals in both the temples depicted Raja Paurava in defeat. The account goes on to tell us that these murals were commissioned by Raja Paurava when news of the death of Alexander arrived in Taxila. Consider: Alexander was dead in distant Babylon, his Greek garrisons in the Sindhu Valley had deserted and Paurava was now the unquestioned master of this country. As sole sovereign, he could have ordered the murals to turn history around and depict him in glorious victory and Alexander in abject and shameful defeat.

But the Punjabi king was not just great in physical stature; he possessed also a soaring spirit and largesse of the heart that few of us know. The king ordered the murals, so it is recorded by Apollonius’ diarist, in order not only to acknowledge his friendship with Alexander, but also to preserve history as it had actually unfolded. In his wisdom the king knew that the creative passage of time was bound to alter history.

When the murals were put up, Taxila was what we today know as the Bhir mound. Two hundred years later, the Indo-Greeks shifted it to the remains we today call Sirkap. It is evident that the murals were admired to be moved to the new city. In the subsequent two hundred odd years the city was rebuilt several times as the various cultural layers show. Each time the murals were safely removed to a new site or they would not have survived three and a half centuries. Finally, in 25 CE Taxila was levelled by a severe earthquake. And when nineteen years later Apollonius arrived, the city was being rebuilt under a Parthian king and the murals had faithfully been reinstalled at the brand new temples. History was not permitted to be tainted.

We do not celebrate Paurava; we name no roads after him and do not teach our children of his lofty character because he shines in our pre-Islamic darkness. But can we today name even one leader possessed of just a shadow of the integrity and character shown by Raja Paurava?

Wednesday, November 14, 2007

The View from India

Where have all the general’s cheerleaders gone?

Part-1

Arun Shourie

Posted online: Tuesday, November 13, 2007 at 0000 hrs IST

http://www.indianexpress.com/story/238378.html

The only persons who could have been surprised by what Musharraf has done are the Americans - who had invested everything in him, and as a consequence just would not see - and Musharraf’s acolytes here in India. Here is one of the most deceitful men we have had to deal with. It is not just that he was the architect of Kargil. Here is a general who insisted that the Pakistani army had nothing to do with Kargil, so much so that he did one of the most dishonourable things that any armyman can do: he refused to accept bodies of soldiers who had died in the operation he had himself planned. And yet the same man claims in his book that Kargil was one of the most successful operations of the Pakistani army! Here is a man who has repeatedly dishonoured his word — pledged to the people of Pakistan, to its courts — about sticking to his office. Here is a man who has repeatedly issued decrees exempting himself from law, from his pledged word. Here, then, has been a personification of deceit. And yet, what a buildup he has had in India — eulogising him has been almost a fashion-statement among many Indian journalists.

And not just among journalists. The very highest in this government allowed themselves to be persuaded by the Americans that we should do something that would strengthen Musharraf, as he was the best, it would seem the only option for us. Of course, they were nudged into accepting American ‘advice’ by that one mental ability they have in abundance — the ability to conjure wishfulfilling thoughts, thoughts that exempt them from standing the ground. This combination — American ‘theses’ and conjured rationalisations — led them to almost make a grand gesture of Siachin to bolster Musharraf, and yet again buy ‘peace in our time’, and that too under the exact camouflage that an American think-tank had stitched up. We have to thank Musharraf: by the morass he has created for himself, he has saved us from our do-gooders.

Yet his cleverness had convinced me long ago about the pass he would reach. For, in the end, few things do a ruler in as surely as cleverness. This is especially so when cleverness is combined with audacity, the ‘commando’s audacity’ that so many among our chatterati came to admire in Musharraf. For this audacity spurs the person to, among other things, lie outright. Soon, though not soon enough, karma catches up. A stage arrives when everything such a ruler does, recoils.

If he moves against the Taliban, he is in trouble. If he does not, he is in trouble. If he does not let American forces chase the Taliban into Pakistani territory, he is in trouble. If he lets them do so, he is in deeper trouble. If he does not storm the Lal Masjid, he is in trouble. If he does, he is in deeper trouble. If he does not remove the chief justice, he is in trouble. If he removes him, his troubles are just beginning. If he gives up his uniform, he can’t rely on the army. If he does not, he can’t rely either on his nemesis, the Supreme Court, or his sole prop, the Americans. If he lets Nawaz Sharif stay, he is in trouble. If he does not, he is in trouble. If he rigs elections again, he has to rely even more on the religious parties and fundamentalists, and he falls deeper in trouble. If he does not rig them, he is finished. Unless he throws the judges out, he is out. Now that he has thrown them out, even his patrons are insisting he bring them back — ulti ho gayin sab tadbirein — every stratagem has boomeranged — kuchch na dawa ne kaam kiya — no potion works!

Once a ruler reaches this pit, anyone and everyone who associates with him, gets tarnished. Americans and Musharraf got conflated: Musharraf came to be seen as the stooge of the Americans; Americans came to be seen as the ventriloquists. Whatever he did was attributed to them: ‘He could do none of this but for the fact that the Americans are behind him.’ And whatever the Americans did came to be pasted on him. As they came to be seen to be waging an out-and-out war against Islam, he came to be seen as the instrument of the enemies of Islam. Convinced, though, they have remained that he is indispensable for them, even the Americans came to realise the heavy cost that association with him was bringing upon them. But the Chinese came to suffer too: they were seen to have been the immediate trigger for the assault on the Lal Masjid, as it followed the kidnapping of Chinese women on the charge that they were running a brothel in Islamabad. (For their part, the Chinese have been increasingly concerned about the Uighurs who have been receiving training in Pakistani madrassas and terrorist camps.) The Saudis too, were shocked by the wave of resentment that hit them upon their being parties to the deportation of Nawaz Sharif. This was one of the main reasons for their subsequent decision to endorse Sharif’s proposal that he return.

And so did everyone within Pakistan who was associated with Musharraf. The ‘Q’ in the name of the faction of the Muslim League that had walked over to him — the PML-Q — came to stand not for ‘Quaid’ after Jinnah, but for an abuse. Look at Benazir till the attack on her procession. She lost heavily when it became known that she had struck a deal with Musharraf. Of course, the ignominy was compounded by two factors: as the deal was seen to have been authored by the Americans, it was contaminated from the very start. Worse, it became known that Benazir had been negotiating terms with Musharraf even as she was signing the Charter of Democracy with Nawaz Sharif — a charter in which both of them pledged that they would never have anything to do with a military dictator. It is only the attack on her procession, and the subsequent snuffing out of the Constitution that has helped restore some of her reputation. But no institution has suffered as much by association with Musharraf as the army: as he came to be seen as the instrument of the enemy, the army, which he controlled, came to be seen as the instrument of the instrument of the enemy...

What a pass for a ruler to reach.

And rulers are brought to this pass by their own stratagems. No ruler after Zia ul Haq gave as big a boost to religious parties and to terrorist groups as Musharraf. It is because of the way he rigged the assembly and provincial elections and the alliance he formed with them that the religious parties — which used to get 5 to 7 per cent of the popular vote — got to form governments in NWFP as well as Balochistan, and to become such a significant factor in the National Assembly. The consequence was as predictable as it has been disastrous. With governance in the hands of religious parties, for instance, the Taliban and Al Qaida acquired an open field in NWFP, and from there into FATA.

Similarly, his premise — one that he set out in as many words — that jihad is an instrument of state policy, and the way he patronised and facilitated terrorism in Kashmir, for instance, has had the same consequence. In her recent study, The Counterterror Coalitions, Cooperation with Pakistan and India, Christine Fair puts it well: one consequence of the jihad in Kashmir and that for the acquisition of Afghanistan, she writes, has been that ‘the concept of jihad has attained an unassailable stature,’ and ‘the political capital’ of groups engaged in it has multiplied several fold. And you can see the end result, even for Musharraf: recall the way he and his government remained paralysed for months in the face of what was being done in and around Lal Masjid. Second, she points out, it has meant that organised criminal groups have been able to extend their operations and reach within Pakistan itself under the banner of jihad. Third, over the past few years, new alliances and coalitions have come to be formed among the various groups. The operational consequence of the latter is just as evident, and it is one of the things that eventually led even his patrons in the US to conclude that he was not doing enough to curb terrorists: when the US or NATO allies were told that steps had indeed been taken against the terrorist groups whom they wanted brought to heel, they were soon disillusioned. And for the obvious reason: when one of the groups was targeted, all that its members had to do was to shift to the adjacent group in the coalition.

Two other features broke through during the last few months: that Musharraf was losing control, and that he had lost touch with what was happening. As for the first, recall how, for months and months, fundamentalists from the Northwest could go on piling up arms in the Lal Masjid right in Islamabad — and the military dictator with all his intelligence agencies should not have known. As for losing touch, recall how gravely Musharraf misjudged the way the public would react to the sacking of the chief justice.

Lessons for us

There has been a veritable industry in India urging concessions: when Pakistan or a ruler of Pakistan has appeared strong, when terrorism sponsored by it and him has been at its murderous height, concessions have been urged on the ground, “but how long can we live with a permanently hostile neighbour?” When he has been facing difficulties, the same concessions have been urged on the ground, “he is our best bet.” Such specious reasoning has almost prevailed when we have had, as we have now, a weak and delusional government, a government that does not have the grit to stay the course; when we have a government over which suggestions from abroad have sway of the kind they have today; when we have a government the higher reaches of which are as bereft of experience in national security affairs as in the government today. We must never sacrifice a national interest in the delusion that someone is the ‘best bet’ — he will soon be gone, and our interest would have been sacrificed in perpetuity. Nor should we ever sacrifice an interest in the delusion that doing so will assuage that ruler, country or ‘movement’.

The concession will only whet his appetite. To the ruler/country/movement, it will be proof that he can extract the next capitulation. Second, we should think for ourselves, and not be led by others, howsoever powerful they may be. One of the great strategic blunders of the US in regard to its ‘War on Terrorism’ has been to have believed, indeed to have proclaimed, that Musharraf is indispensable. The consequence has been predictable. Their having come to think of him as indispensable, Musharraf has done what suited him, not that war: look at the selective way in which he went after the terrorists. He first targeted only the Al Qaida in whom the Americans were interested; then, those who targeted him; then those who targeted the Pakistani state. The organisations that he, his army, the ISI had reared for breaking India, he left alone. The Americans had to shut their eyes. “You are putting all your eggs in one basket,” they were told. “But there aren’t that many baskets in Pakistan,” they said. Soon, they got their desserts too, and twice over. First, as was noted above, given the fungibility among such groups, the former set of terrorists had just to don the garb of the latter and continue to recruit, to rearm, to regroup. And then, Musharraf having come to be seen as merely their stooge, he couldn’t keep the system going — for them any more than for himself. In a word, powers, howsoever well endowed, can be dead wrong in their assessment even of their own interest. In any event, it is their own interest they shall be pursuing. Their own interest as perceived by a handful. Their own interest as perceived by a handful at that moment.

Today Saddam is good because he is a counter to Iran; tomorrow he is evil. Today the Taliban are mujahideen, freedom fighters, as they are necessary for throwing the Soviets out; tomorrow they are evil. Today the Kurds are good as a counter to Sunnis in Iraq; tomorrow they are evil as the fellows are dragging Turkey into the arena... This is not to blame the Americans or anyone else: through such twists and turns they are merely pursuing their interest. The lesson is for us: how very wrong, how very shortsighted it would be for us to outsource our thinking to others.

The even more important lesson is illustrated vividly by the relief we have had in Kashmir in the last few months days. As Balochistan, NWFP, and now FATA have flared up, Pakistan has had to withdraw its troops and other resources from its border with India to its western border. The killings and explosions in Kashmir have gone down. Just a coincidence?

Now notice two things. First, as Pakistan has had to move its troops away from the border with Kashmir, an orchestra has started in India demanding that we thin our troops in Kashmir: just another coincidence? Second, recall the ‘remedies’ that our secularists have been urging — ‘autonomy’ and the rest. “The Kashmiris feel alienated,” they have been declaiming. “That is the root-cause of terrorism... give them autonomy...” A formula-factory came into being: ‘Musharraf’s 7-regions’ formula...’

None of those ‘solutions’ has been put in place. Yet, the killings have gone down. Which is the medicine that has worked? The potion — ‘autonomy’ — we did not administer? Or the medicine that Pakistan has administered to itself? That it has got into trouble on its western borders? A lesson there...

Pakistan beyond Musharraf

Part II

Arun Shourie

Posted online: Wednesday, November 14, 2007 at 0000 hrs IST

http://www.indianexpress.com/story/238744.html

Pakistan has lost control over half its territory. In all probability it will regain that control at some time in the future. But the fact that half of the country’s territory is today outside the writ of the Pakistani state shows how far things have been allowed to fall.

Information that reaches India suggests that the troubles in Balochistan are much worse than what becomes public knowledge — a determined effort has been made to black out what is happening there. In the northwest, the Maliks and Khans were already losing out to the Taliban — the latter had begun replacing them even in governmental committees, a better way to route outlays to itself. Since then, these persons as well as the political mullahs through whom the area was being controlled have come to be viewed as instruments of the enemy. Hence, administration has crumbled. Two ‘accords’ and a third attempted ‘accord’ have come to nothing. Each ‘accord’ was seen as, and was in fact an acknowledgement that the Pakistani army was not able to contain the situation: in the Miramshah Accord, for instance, the most recent one to unravel, the tribals agreed not to attack Pakistani troops in return for the withdrawal of troops from the region. And in return for tribals being allowed to continue to bear arms, the government agreed to release 165 tribal militants and provide handsome ‘compensation’. Each ‘accord’ has been terminated at the will of the tribals and the army has been able to do nothing in the matter.

The sway of the Taliban has now spread to FATA. In this region, the three agencies most affected are south Waziristan, north Waziristan and Bajaur. But Talibanisation has started spreading from FATA to the adjacent ‘settled districts’ of NWFP. In places like Tank, Dera Ismail Khan, Swat, and so on, the Taliban roam the streets freely and enforce their ‘values’. Barber shops and video parlours have been shut down. Men are required to grow beards. Music is banned. Girls have been prohibited from attending school: ‘the card’ is a dread — a postcard is delivered at the house with the photograph of a severed head on one side, and, on the other, a simple note: ‘your daughter XYZ, goes to school ABC, located at...’ Parents have to take their child out of school or risk her life or swiftly dispatch her to some other town...

To confound matters, the only instrument through which the areas could be retrieved, the army, is showing signs of strain. It has suffered major casualties and embarrassing reverses. In a series of the most telling events, large numbers of soldiers have ‘surrendered’. In the first instance, close to 300 were reported to have been ‘kidnapped’. They were led by a colonel at the time. There were four officers among them. Not one casualty occurred. The whole lot just got ‘kidnapped’ or they surrendered. Since then, the sequence has been repeated at least twice — with two differences: the tribals called the media over to photograph the soldiers they had captured, and, after making them swear never to fight fellow Muslims again, released them.

By now, the problem is structural. That is, it is not just the mistake of a Musharraf. A quarter of Pakistan’s army consists of Pashtuns. Not just that, major operations are being carried out by the Frontier Corps. This consists of locally recruited Pashtun soldiers, officered by Punjabi army officers. On the other side, earlier, the fighting was largely being done by foreign militants — Chechens, Uzbeks, Arabs. They were being supported by the Taliban. Now it appears that entire tribes and sub-tribes are rising in revolt against the army. Pashtun soldiers are chary of fighting persons from their own tribe, and just as nervous of fighting Pashtuns from other sub-tribes or tribes, for they know that doing so could well trigger a cycle of revenge, a cycle that will last for generations. Nor would sending units of Punjabis help matters: quite the contrary, doing so would transform the hostilities into an ethnic conflict — Punjabis killing Pashtuns will stoke the flames even more vigorously.

But this development should not cause surprise, as my friend, Sushant Sareen, who follows developments in our neighbours almost by the hour, points out. The army is itself steeped in the culture of jihad, and so will naturally be reluctant to kill those who are, after all, sacrificing their lives in jihad. Even in 1971, the situation was not as grave from a soldier’s point of view as it is now: in that war, he, a Punjabi, was killing Bengalis. Today Pashtuns are being set to kill Pashtuns. Moreover, unlike the Bengalis in 1971, these groups fight back: they are well-armed; they are very well trained; their motivation is stronger than that of even the indoctrinated Pakistani soldier; they are masters of their terrain; they are not ‘primitives’. On the contrary, they are extremely sophisticated in their tactics and strategy.

Could there be more than just morale here? Could it be that because of its pervasive involvement in the economy and administration, because of the enormous collateral perquisites that are given to officers — from plots to control of ‘heavy’ enterprises — the army, in particular its officer class, has softened? The performance of the army in Kargil, in Balochistan and now in NWFP certainly suggests that this is possible. The main debility, however, is different: the army has been reared to kill and prevail over ‘imbecile kafirs’, and it must balk at killing fellow Muslims.

It is often suggested that after 9/11 and his decision to join the American war, Musharraf cleaned out the bearded generals. He may have shunted out some individuals. But the American war and joining it have certainly put the ‘moderates’ in the army on the defensive. The Islamists have been proven right. One minor indication of this was visible in the Lal Masjid incident. Here is a mosque not in the far away, wild tribal areas, but in Islamabad itself. The entire country is under army rule. The ISI as well as intelligence agencies of the army itself are in each nook and cranny of the country. How could such a vast armoury have been accumulated in the mosque and the adjacent madrassa without the complicity of elements inside these organisations?

So, we have, on the one hand, half the territory going out of the writ of Islamabad, and, on the other, the one instrument through which it would have to be wrested back, drooping.

To compound matters, the Taliban are a very different force from what they used to be. They have metamorphosed. Their modus operandi are now very different from what they were: as has been correctly noted, today, Pakistan is second only to Iraq in suicide attacks. Similarly, the Taliban used to hit and run. Now they engage in extended, fixed battles. More important, the aim of the Taliban now is not that of a local militant group. Nor, as Sushant Sareen writes, is their aim to undo Pakistan. Their aim is to take over Pakistan and Afghanistan, at least large parts of these. And from these areas as a base, to carry forward the jihad to convert lands farther and farther away that are today the dar ul harb into the dar ul Islam. Hence, there can be no doubt at all that, after consolidating their position in the trans-Indus regions, they will extend their ideology and operations into Punjab and Sindh. And recent attacks and explosions show that they already have the capacity to reach into the very heart of Pakistan. Incidentally, this has been a major strategic mistake of the West, one of many that is, to have shut its eyes to the fact that the Taliban was getting revived and transformed, and, instead, to have allowed itself to be diverted by the few ‘Al Qaida’ operatives that Pakistan has from time to time handed over.

There is an even more ominous transformation for Pakistan: the Islamic zeal of Taliban has got fused into Pashtun nationalism. Few of us realise that while there are 12 million Pashtuns in Afghanistan, there are 25 million in Pakistan. Historically, leadership has rested with the Afghan Pashtuns. But this is shifting to Pak-Pashtuns now — contrast the sway of warlords in FATA and NWFP with the shrunken, tenuous existence of Karzai: they roam freely, they dominate their areas while Karzai is confined to Kabul, and, even within Kabul, he is dependent on the Americans for even his personal safety. The Pashtuns have never accepted the Durand Line as a divide. Successive jihads — first against the Soviets and now against the Americans — have erased it on the ground. Even de jure, no Afghan government, not even the Taliban government that was the creature of Pakistani agencies, accepted it. In any case, the hundred years for which it was delineated are long gone. The Afghans have long demanded that the line should be further south, as far south in fact as Attock.

A potent mix: a Taliban fired by the zeal to establish Islam by fomenting the ‘Clash of Civilisations’ that others dread; Pashtun nationalism demanding a Pakhtunistan with territory from both Afghanistan and Pakistan; a quarter of Pakistan’s army and almost all of the Frontier Corps deployed in the region, Pashtun. And that is just one problem in one arena.

Today, even as the Pakistani army is sent out to combat them in FATA and NWFP, Pakistan continues to aid the Taliban in their forays into Afghanistan. And for the obvious reason: it is convinced — who would not be? — that the NATO forces, in particular the Americans will leave sooner rather than later; Pakistan would want its agents to take over Kabul and thus reacquire the ‘strategic depth’ vis a vis India, the acquiring of which a few years ago it had hailed as one of the greatest feats of its strategic planning. But Pakistan is not the only source from which the Taliban get aid. Information we receive suggests that, though they are fervent Sunnis, they are getting help even from Shia Iran. And for this too the reasons are obvious: for Iran today, any and every group that will hobble the US today is a confederate; second, while they are at it, Iran wants them to eliminate those of its dissidents who have taken shelter in southwestern Afghanistan. More than the aid they receive, the Taliban today have become self-financing: as has been pointed out in General Afsir Khan’s important journal Aakrosh, the Taliban are being much more nuanced about opium and heroin this time round. In their earlier reign, they had banned hashish, not heroin, as the former is what the locals were consuming. This time round they are allowing greater latitude in regard to both as they have realised that drugs provide income to farmers and thus relieve the Taliban of a responsibility, and at the same time, the produce are an unfailing source of revenue. Contrast this with the dilemma that hobbles American and NATO forces: they are not able to provide alternative sources either for employment or for income to the local population but if they stamp out opium cultivation, they alienate farmers; on the other hand, if they allow it to grow, they help finance the Taliban.

Thus, Pakistan is today feeding with one hand the Taliban it seeks to crush with the other; second, the Taliban receive aid and acquire resources from other quarters. But the main problem is different and goes deeper. With what legitimacy can the government in NWFP, FATA, Islamabad crush them? All that the Tehrik-e-Nifaz-e-Shariah-e-Mohammadi is demanding, after all, is that the shariah be enforced: with what face can parties that have come to power in the name of Islam in NWFP — the religious parties — crush them for this? Indeed, Pakistan having been proclaimed an Islamic state, shariah courts having been set up since Zia’s time, with what legitimacy can Islamabad move to crush the cleric who is enforcing the shariah in FATA? As it moves to kill them in any case, Musharraf’s army becomes an instrument of ‘the enemies of Islam’.

That problem goes beyond Musharraf and his army. It permeates every pore of Pakistan. Pakistan having declared itself to be an ‘Islamic state’, the ‘moderates’ on whom the West rests its hopes, as do the wishful in India, just cannot stand up to the mullahs: the latter have to merely keep reciting verses from the Quran and repeating hadis; they have merely to ask, as they do at every turn, “if the object was to establish Pakistan as a secular state, as a state indifferent to Islam, as one in which not the shariah but some alien law shall rule, what was the point of creating Pakistan, what was the point of partitioning India?” “How can preaching religion be terrorism?” they demand. Moreover, the ‘moderate’ politicians are themselves seen as nothing but, as has been correctly observed, ‘democrats of convenience’ — for each of them without exception has in the past turned to and been propped up by the army and ISI. Each has been as corrupt as the other. Each has turned to and struck deals with religious fundamentalists — and this includes not just Musharraf in whom our commentators discern so much secularism; it includes Nawaz Sharif and Benazir. The lawyers did not keep politicians away from their agitation without reason.

In a word, the Taliban are not the cause of the Talibanisation of Pakistani society. They are the result. The madrassas are not the only ones that indoctrinate their wards in extremism; as the excellent studies by the Pakistani historian K.K. Aziz in the early 1990s, and by Islamabad’s Sustainable Development Policy Institute more recently have shown, government schools indoctrinate students no less — from class 2 onwards — in the blessings and glory that accrue from jihad and shahadat.

It is obvious that Musharraf’s ‘emergency’ has had nothing whatsoever to do with the real problems that Pakistan faces. First, he has contributed as much to inflaming them as anyone. Second, if terrorism in the NWFP and FATA are the target, why remove the judges? Why throw human rights activists into jails? Third, look at what he and his ministers began saying the moment Bush and others called him: elections in February 2008, of course I will give up my uniform, ‘emergency’ will be ended within weeks — is it any one’s case that the tribals in NWFP and FATA will be brought to heel in a few weeks?

So, his ‘emergency’ has been just to save himself from the Supreme Court. But equally, for the kinds of reasons enumerated above, removing him is not going to solve the problems in which Pakistan finds itself today. Most certainly not for India.

For Pakistan is today a dictatorship in the grip of the army and ISI because of the neglect of institutions over sixty years. Pakistan is today a Talibanised society as the culmination of a choice it made sixty years ago — of being an Islamic state. Once the dust kicked up by Musharraf settles, whoever is in power in Islamabad will gravitate to the old, accustomed conclusion: there is only one way of coping with the jihadis — deflect them to India...

But who has that distant a horizon?

Part III

Arun Shourie

Posted online: Thursday, November 15, 2007 at 0000 hrs IST

http://www.indianexpress.com/story/239136.html

It really is ‘crunch time’ for Pakistan, says a keen observer: the mere installation of a civilian government will not change the character of Pakistan. In a sense, even under Musharraf, a civilian government has functioned — there has been a cabinet headed by Shaukat Aziz, a Citibank executive, no less; there has been an elected assembly; a ‘normal’ political party, the PML-Q, has fronted for Musharraf; there has even been a free press. And yet things have reached the pass they have.

A much more fundamental choice confronts Pakistan as well as the West: Pakistan’s rulers and its props have to choose — to either have the country lunge for the jihadi option or to wage an all-out struggle to root out the causes of the jihadi culture; to either hand the country over to extremists or to crush them completely. The problem relates not to whether the government is military or ‘civilian’. Even in the latter, given the way things are in Pakistan, the army and agencies like the ISI will control all vital decisions and policies, as they have done in the previous civilian governments. It relates to the nature of such government as controls affairs. It relates even more fundamentally to the nature of the society from which the government must necessarily be formed and which it has to steer.

As we have seen, the nature of Pakistan’s society today — in which, to recall just one symptom, jihad and shahadat have such exalted status, in which enmity to India has such a central place — is the result of developments over 60 years and more. Three features of the ‘solution’ that is necessary are at once evident.

First, as analysts like Ajai Sahni, Sushant Sareen and others correctly point out, it will entail deep, very deep surgery, a complete reversal. It will require not just that jihadi groups be absolutely crushed; but, in addition, that the army is completely subordinated to civilian authority; that constitutional government, and the rule of law are instituted; that the ISI in its present form is virtually eliminated; that the curricula of madrassas and government schools are overturned; that the objective of wresting Kashmir is abandoned; that the premise, to use Musharraf’s enunciation, that terrorism and proxy-war are ‘instruments of state policy’ is shed completely; that Pakistan comes to reconcile itself to more realistic notions of the extent to which it can ‘project’ its power; that either the populace goes back on the basic article of faith, ‘Pakistan is an Islamic state’, or that Islam is so thoroughly recast as to be almost unrecognisable.

But such an about-turn requires leaders of the highest legitimacy, it requires an intellectual ferment, it requires robust reformers. None of the three is around. The leaders are dwarfs, especially when it comes to religious discourse — none of them could hold her or his own even in front of the run-of-the-mill maulvis who crowd Pakistan’s Islamic TV channels. There is no intellectual ferment within Islam as it is practiced in South Asia. As for reformers, Iqbal is long gone, Maulana Maududi prevails.

Moreover, there are so many coils in which the current world-view is entangled. Recall, for instance, the deep links that Middle Eastern regimes have with the jihadi groups in Pakistan. Will they forego the links and the options that the links give them? The option, for instance, of directing the revolutionary zeal of fundamentalists to regions outside their countries and thus saving themselves? Within Pakistan, such surgery will go against the indoctrination of the last 60 years. The difficulties entailed in doing so, especially in the rural areas, can scarcely be imagined. There is another factor: Pakistan has relied on and stoked Islamic identity to neutralise ethnic nationalisms — Baloch, Pashtun, Sindhi, Mohajir. These will erupt even more ferociously than is already the case were the Islamic quotient in the concept of state to be diluted. In any case, such an exercise cannot even commence until the ruling elite of Pakistan comes to realise that it has no option at all except such a course. The fact of the matter is that, while they appear non-plussed today, the elite are far from such a point — on the contrary, they are confident that the West will, and that China and Saudi Arabia in the end will allow them, even assist them to go on as they have been doing. On the other side, with the breakdown of governance, security, even basic services, people are much more likely to leap for the messianic alternative that is being proffered by fundamentalists than to go along with such fundamental wrenching of everything they have been fed for 60 years.

The first point that stands out about what is necessary, therefore, is that, on the one hand, only deep surgery will work, and, on the other, there are almost insuperable difficulties in attempting it. The second feature is just as evident: even if it were to be attempted, such a solution will take one generation, if not two. And, third, neither the rulers of Pakistan nor the West — in particular not the US — have that far a horizon.

True, civil society has to be strengthened, the reasoning in the West is liable to go. But we need the army today, and the army feels that a strengthened civil society will necessarily weaken its hold... True, all these basic reforms should be initiated over the long run, the reasoning will go, but the army has to be humoured today — let us postpone these reforms till tomorrow — why not first start a pilot-project and see how things work out... And as the army will not be humoured by arms needed to fight the terrorists, we must give it the arms it wants — F16s if F16s are what they want — is it any surprise that of the eleven billion dollars that have been given to Pakistan as ‘aid’ since 9/11 by the US alone, only one billion are reported to have gone for ‘development’? Is it any surprise that, while military aid has been given ostensibly for fighting the Al Qaeda in the mountains, much of it has consisted of weapons systems that enhance Pakistan’s offensive capacities vis a vis a country like India?

This is exactly what the nostrums that are being pedalled today show once again. You must hold elections as you promised, Bush tells Musharraf. We can be quite confident that exactly that was Musharraf’s preferred option even when he was giving in to American pressure and striking a deal with Benazir. Get her to sign the deal. That will at once break the political configuration that the Charter of Democracy presaged. Then do the customary thing: rig the elections so that no party, certainly not Benazir’s PPP, wins an outright majority. The new ‘civilian’ government will then have to take your own surrogates on board. And you could certainly tell Benazir, “With a hung assembly, what can I do? I can’t amend the Constitution to remove the bar on your becoming PM for a third time...” Musharraf would have had little difficulty in ensuring this outcome — his Election Commission had already begun the process: the number of voters had suddenly fallen by several million, by so many that the number of voters for the elections scheduled for 2008 was less than the ones that were there in 2002; that the electoral rolls would have to be ‘corrected’ at top speed would give the agencies and the army all the opportunity they needed for ‘correcting’ them correctly! There would have been no difficulty, it is just that a random variable barged in, the chief justice and the suddenly independent court!

You have to give up your uniform, Bush tells Musharraf. Assume he does so, and Benazir becomes PM. As Wilson John and others have remarked, she will be one of a trio — Musharraf and Kiyani, the army chief, will be the two other members. She will almost certainly be kept out of the vital areas — foreign policy, in particular everything concerning relations with the West, India and Afghanistan; the fight against terrorists; nuclear weapons... This, after all, is exactly what was done in the past — and not just with her. In any event, the provision that allows the president to dismiss the elected government — Article 58(2) of the Constitution — would be still on the statute book, indeed it has been formalised once again in Musharraf’s Legal Framework Order — the precise provision that was used by a previous president, Ghulam Ishaq Khan, to dismiss Benazir earlier. Even if none of this comes to pass, and the trio comes to function, she, or in her stead some other civilian prime minister, will be the weakest of the three. As has been rightly pointed out, to stand up to the president, she/he will have to seek the help of the army chief. Even if she/he gets this help, the hold of the army over governance will be reinforced. And yet, everyone is fixated on, ‘you have to give up your uniform,’ as if it were a sovereign remedy.

Thus, the ‘solutions’ that are being pushed are liable to turn out to be merely pro-forma. Others are liable to be worse. One of the problems always is that those who have a particular thing make themselves believe that that thing will turn the trick. Those who have superior technology think that technology will solve the problem — witness Iraq. Those who have money think that money will solve the problem: announcements from Washington suggest that $750 million are to be pumped into the NWFP and FATA to ‘develop’ them; as Jagmohan has documented in the case of Kashmir, as K.P.S. Gill has pointed out in the case of left-wing violence and other insurgencies, we can be certain that the funds will end up with the terrorist groups and will finance the insurgency further.

The other nostrum — ‘modernise madrassas’, introduce science, computers, English — will fare no better. Quite the contrary. As Ajai Sahni writes, such steps will only help close a ‘competence-deficiency’. Today the would-be graduate of these institutions has some difficulty, for instance, in blending into the country he is tasked to target. Having been taught English, being familiar with science and modern technologies, he will be all the better able to use those technologies, he will be better able to blend into western societies for carrying out the operations for which he has been primed.

Hence, there is every likelihood that pseudo-reforms will be pushed, and little likelihood of the fundamental reforms that are required. At each turn, the latter set of reforms will be begun nominally, and soon postponed to the indefinite future. And every step that will be taken to put existing realities to work will only reinforce the current configuration.

The other development that is likely in the coming two or three years, if not sooner, will be even more consequential for us. American and NATO forces will retreat — from both Afghanistan and Iraq. They will retreat in defeat. We must bear in mind that American forces did not lose a single engagement in Vietnam. Yet they had to retreat. The Soviet forces did not lose a single engagement in Afghanistan. Yet they had to retreat.

This retreat will provide a tremendous boost to fundamentalist forces. While they will continue to try to penetrate the US as well as target American installations abroad, their immediate targets are likely to be one or two regimes in the Middle Eastern — regimes that have thus far been buying security by exporting revolutionary impulses; Europe — which is still caught in effete notions of political correctness, and in which there now is a quantum of population that is large enough to be a political force, as well as to contain within it the few who will be hosts to and provide members for fundamentalist cells: intelligence sources state that volunteers who left for training in Iraq and Pakistan are now returning for carrying out operations in Europe itself. But the most likely of all potential targets will be soft states like India.

That is the prospect for which we must prepare — a Pakistan the nature of whose society does not change, and a triumphalist extremism.

A host of steps is necessary for meeting that prospect — from shedding the perverse nonsense that leads so many to lionise those who assault our country: witness the campaigns for Afzal Beg; to exhuming the ideological bases of Islamic extremism; to showing up the pretensions of ‘Islamic states’ — how come, as Pervez Hoodbhoy, the Pakistani physicist asks, that such states are among the richest in the world and yet their work in science and technology is so far behind? How come, as Maulana Wahiduddin has asked, while it is claimed again and again that no religion gives as exalted a place to women as Islam does, the position of women in every Islamic state is woeful? For exhuming the ideological bases and nailing such pretensions to reviving the Northern Alliance so that, even if the Taliban win, they remain busy within Afghanistan; to supporting groups that are struggling for the most elementary rights in POK, in Gilgit-Baltistan, in the northern territories of Pakistan; to ensuring honest and effective governance in Kashmir... first we have to clear our minds. First we have to give up what has become our fixed policy — hoping that something will turn up.

Till then, let us be clear, the best possible outcome for us, one for which we can do little, is that a discredited and besieged Musharraf continues in office — so that the fount of decisions remains preoccupied with his own problems. And that the Pakistan army remains encoiled in protracted and bloody hostilities with the extremists that it and ISI, and so on, have reared — so that the trust and working alliance between them is ruptured. If prayers are to be the only policy we are capable of, pray for these, not for democracy!

Wednesday, October 3, 2007

Pakistan At Sixty

Tariq Ali

http://gess.wordpress.com/2007/09/28/pakistan-at-sixty/

Pakistan is best avoided in August, when the rains come and transform the plains into a huge steam bath. When I lived there we fled to the mountains, but this year I stayed put. The real killer is the humidity. Relief arrives in short bursts: a sudden stillness followed by the darkening of the sky, thunderclaps like distant bombs and then the hard rain. Rivers and tributaries quickly overflow; flash floods make cities impassable. Sewage runs through slums and posh neighbourhoods alike. Even if you go straight from air-conditioned room to air-conditioned car you can’t completely escape the smell. In August sixty years ago, Pakistan was separated from the subcontinent. This summer, as power appeared to be draining away from Pervez Musharraf, the country’s fourth military dictator, it was instructive to observe the process at first hand.

Disillusionment and resentment are widespread. Cultivating anti-Indian/anti-Hindu feeling, in an attempt to encourage national cohesion, no longer works. The celebrations marking the anniversary of independence on 14 August are more artificial and irritating than ever. A cacophony of meaningless slogans that impress nobody, countless clichés in newspaper supplements competing for space with stale photographs of the Founder (Muhammad Ali Jinnah) and the Poet (Iqbal). Banal panel discussions remind us of what Jinnah said or didn’t say. The perfidious Lord Mountbatten and his ‘promiscuous’ wife, Edwina, are denounced for favouring India when it came to the division of the spoils. It’s true, but we can’t blame them for the wreck Pakistan has become. In private, of course, there is much soul-searching, and a surprising collection of people now feel the state should never have been founded.

Several years after the split with Bangladesh in 1971 I wrote a book called Can Pakistan Survive? for Penguin. It was publicly denounced and banned by the dictator of the day, General Zia-ul-Haq, but pirated in many editions. I had argued that if the state carried on in the same old way, some of the minority provinces left behind might also defect, leaving the Punjab alone, strutting like a cock on a dunghill. Many of those who denounced me as a traitor and a renegade are now asking the same question. It’s too late for regrets, I tell them. The country is here to stay. And it’s not religion or the mystical ‘ideology of Pakistan’ that guarantees its survival, but its nuclear capacity and Washington.

On the country’s 60th birthday (as on its 20th and 30th anniversaries), an embattled military regime is fighting for its survival. There is a war on its western frontier, while at home it is being tormented by jihadis and judges. None of this seemed to make much difference to the young men on motorbikes who took over the streets of Lahore in their annual suicide race. It seems the only thing worth celebrating is the right to die. Only five managed it this year, a much lower figure than in the previous five years. Maybe this is a rational way to mark a conflict in which more than a million people hacked each other to death as the decaying British Empire prepared to scuttle off home. On the eve of Partition a cabinet meeting in London was devoted to the growing crisis in India. The minutes reported: ‘Mr Jinnah was very bitter and determined. He seemed to the secretary of state like a man who knew that he was going to be killed and therefore insisted on committing suicide to avoid it.’ He was not alone.

Now yet another uniformed despot was taking the salute at a military parade to mark independence day in Islamabad, mouthing a bad speech written by a bored bureaucrat that failed to stifle the yawns of the surrounding sycophants. Even the F-16s in proud formation failed to excite the audience. Flags were waved by schoolchildren, a band played the national anthem, the whole show was broadcast live and then it was over.

The European and North American papers give the impression that the main, if not the only, problem confronting Pakistan is the power of the bearded fanatics skulking in the Hindu Kush, who as the papers see it are on the verge of taking over the country. In this account, all that stops a jihadi finger finding the nuclear trigger is Musharraf. Alas, it now seems he might drown in a sea of troubles and so the helpful State Department has pushed out an over-inflated raft in the shape of Benazir Bhutto.

In fact, the threat of a jihadi takeover of Pakistan is remote. There is no possibility of a takeover by religious extremists unless the army wants one, as in the 1980s, when General Zia-ul-Haq handed over the Ministries of Education and Information to the Jamaat-e-Islami, with dire results. There are serious problems confronting Pakistan, but these are usually ignored in Washington, by both the administration and the financial institutions. The lack of a basic social infrastructure encourages hopelessness and despair, but only a tiny minority turns to jihad.

During periods of military rule in Pakistan three groups get together: military leaders, a corrupt claque of fixer-politicians, and businessmen eyeing juicy contracts or state-owned land. The country’s ruling elite has spent the last sixty years defending its ill-gotten wealth and privilege, and the Supreme Leader (uniformed or not) is invariably intoxicated by their flattery. Corruption envelops Pakistan. The poor bear the burden, but the middle classes are also affected. Lawyers, doctors, teachers, small businessmen, traders are crippled by a system in which patronage and bribery are trump cards. Some escape – there are 20,000 Pakistani doctors working in the United States alone – but others come to terms with the system, accept compromises that make them deeply cynical about themselves and everyone else.

The resulting moral vacuum is filled by porn films and religiosity of various sorts. In some areas religion and pornography go together: the highest sales of porn videos are in Peshawar and Quetta, strongholds of the religious parties. Taliban leaders in Pakistan target video shops, but the dealers merely go underground. Nor should it be imagined that the bulk of the porn comes from the West. There is a thriving clandestine industry in Pakistan, with its own local stars, male and female.

Meanwhile the Islamists are busy picking up supporters. The persistent and ruthless missionaries of Tablighi Jamaat (TJ) are especially effective. Sinners from every social group, desperate for purification, queue to join. TJ headquarters in Pakistan are situated in a large mission in Raiwind. Once a tiny village surrounded by fields of wheat, corn and mustard seed, it is now a fashionable suburb of Lahore, where the Sharif brothers built a Gulf-style palace when they were in power in the 1990s. The TJ was founded in the 1920s by Maulana Ilyas, a cleric who trained at the orthodox Sunni seminary in Deoband, in Uttar Pradesh. At first, its missionaries were concentrated in Northern India, but today there are large groups in North America and Western Europe. The TJ hopes to get planning permission to build a mosque in East London next to the Olympic site. It would be the largest mosque in Europe. In Pakistan, TJ influence is widespread. Penetrating the national cricket team has been its most conspicuous success: Inzamam-ul-Haq and Mohammed Yousuf are activists for the cause at home while Mushtaq Ahmet works hard in their interest in Britain. Another triumph was the post-9/11 recruitment of Junaid Jamshed, the charismatic lead singer of Pakistan’s first successful pop group, Vital Signs. He renounced his past and now sings only devotional songs – naats.

The Tablighis stress their non-violence and insist they are there merely to broadcast the true faith in order to help people find the correct path in life. This may be so, but it is clear that some younger male recruits, bored with all the dogma, ceremonies and ritual, are more interested in getting their hands on a Kalashnikov. Many believe that the Tablighi missionary camps are fertile recruiting grounds for armed groups active on the Western Frontier and in Kashmir.

The establishment has been slow to challenge the interpretation of Islam put forward by groups such as Tablighi. Musharraf advised people to go and see Khuda Kay Liye (‘In the Name of God’), a new movie directed by Shoaib Mansoor (who wrote and produced some of Vital Signs’ most successful music). This may not help the film, or the moderate Islam it favours, given that Musharraf’s popularity ratings currently trail Osama bin Laden’s, according to a recent poll, but I went to a matinee performance in Lahore and the cinema was packed with young people. The film is well intentioned, also long-winded and crude. It has, however, had an impact. At least it tries out a few ideas, which is unheard of in a country where the film industry produces nothing but Bollywood-style dross, even if the ideas are limited to the good Muslim, bad Muslim stereotype. Jihadi violence is bad. Music is good and not anti-Islamic. Violence and rape in the badlands of the Pakistan-Afghan frontier are intercut with scenes in a post-9/11 United States, where an innocent Pakistani musician is lifted by intelligence operatives and tortured (these scenes go on far too long). The implication is that each side feeds on the other. It is a prim film and the row of youths sitting behind me clearly wanted some more action on the sex front. When a white female student in Chicago gives the Pakistani musician a present, one of them commented: ‘She’s giving him her phone number.’ If the ushers hadn’t told the youths to keep quiet I might have enjoyed the film more.

One of the main threats to Musharraf’s authority is the country’s judiciary. On 9 March, Musharraf suspended Iftikhar Muhammad Chaudhry, the chief justice of the Supreme Court, pending an investigation. The accusations against him were contained in a letter from Naeem Bokhari, a Supreme Court advocate. Curiously, the letter was widely circulated – I received a copy via email. I wondered whether something was afoot, but decided the letter was just sour grapes. Not so: it was part of a plan. After a few personal complaints, extravagant rhetoric took over:

My Lord, the dignity of lawyers is consistently being violated by you. We are treated harshly, rudely, brusquely and nastily. We are not heard. We are not allowed to present our case. There is little scope for advocacy. The words used in the Bar Room for Court No. 1 are ‘the slaughter house’. We are cowed down by aggression from the Bench, led by you. All we receive from you is arrogance, aggression and belligerence.

The following passage should have alerted me to what was really going on:

I am pained at the wide publicity to cases taken up by My Lord in the Supreme Court under the banner of Fundamental Rights. The proceedings before the Supreme Court can conveniently and easily be referred to the District and Sessions Judges. I am further pained by the media coverage of the Supreme Court on the recovery of a female. In the Bar Room, this is referred to as a ‘media circus’.

The chief justice was beginning to embarrass the regime. He had found against the government on a number of key issues, including the rushed privatisation of the Pakistan Steel Mills in Karachi, a pet project of Prime Minister Shaukat (‘Shortcut’) Aziz. The case was reminiscent of Yeltsin’s Russia. Economists had estimated that the industry was worth $5 billion. Seventy-five per cent of the shares were sold for $362 million in a 30-minute auction to a friendly consortium consisting of Arif Habib Securities (Pakistan), al-Tuwairqi (Saudi Arabia) and the Magnitogorsk Iron & Steel Works Open JSC (Russia). The privatisation wasn’t popular with the military, and the retiring chairman, Haq Nawaz Akhtar, complained that ‘the plant could have fetched more money if it were sold as scrap.’ The general perception was that the president and prime minister had helped out their friends. A frequenter of the Stock Exchange told me in Karachi that Arif Habib Securities (which owns 20 per cent) was set up as a front company for Shaukat Aziz. The Saudi steel giant (40 per cent) is reputedly on very friendly terms with Musharraf, who turned up to open a steel factory set up by the group on 220 acres of land rented from the adjoining Pakistan Steel Mills. Now they own it all.

After the Supreme Court insisted that ‘disappeared’ political activists be produced in court and refused to dismiss rape cases, there were worries in Islamabad that the chief justice might even declare the military presidency unconstitutional. Paranoia set in. Measures had to be taken. The general and his cabinet decided to frighten Chaudhry by suspending him. The chief justice was kept in solitary confinement for several hours, manhandled by intelligence operatives, and traduced on state television. But instead of caving in and accepting a generous resignation settlement, the judge insisted on defending himself, triggering a remarkable movement in defence of an independent judiciary. This is surprising. Pakistani judges are notoriously conservative and have legitimised every coup with a bogus ‘doctrine of necessity’ ruling (although some did refuse to swear an oath of loyalty to Musharraf).

When I visited Pakistan in April the protests were getting bigger every day. Initially confined to the country’s 80,000 lawyers and several dozen judges, unrest soon spread beyond them, which was unusual in a country whose people have become increasingly alienated from elite rule. But the lawyers were marching in defence of the constitutional separation of powers. There was something delightfully old-fashioned about this struggle: it involved neither money nor religion, but principle. Careerists from the opposition (some of whom had organised thuggish assaults on the Supreme Court when in power) tried to make the cause their own. ‘Don’t imagine they’ve all suddenly changed,’ Abid Hasan Manto, one of the country’s most respected lawyers, told me. ‘On the other hand, when the time comes almost anything can act as a spark.’

It soon became obvious to most people in the Islamabad bureaucracy that they had made a gigantic blunder. But as often happens in a crisis, instead of acknowledging this and moving to correct it, the perpetrators decided on a show of strength. The first targets were independent TV channels. In Karachi and other cities in the south three channels suddenly went dark as they were screening reports on the demonstrations. There was popular outrage. On 5 May Chaudhry drove from Islamabad to give a speech in Lahore, stopping at every town en route to meet supporters; it took 26 hours to complete a journey that should take four or five. In Islamabad they plotted a counter-strike.

The judge was due to visit Karachi, the country’s largest city, on 12 May. Political power here rests in the hands of the MQM (Muttahida Qaumi Movement/United National Movement), an unsavoury outfit created during a previous dictatorship and notorious for its involvement in protection rackets and other kinds of violence. It has supported Musharraf loyally through every crisis. Its leader, Altaf Hussain, guides the movement from a safe perch in London, fearful of retribution from his many opponents were he to return. In a video address to his followers in Karachi he said: ‘If conspiracies are hatched to end the present democratically elected government then each and every worker of MQM . . . will stand firm and defend the democratic government.’ It was typical of him. On Islamabad’s instructions, the MQM leaders decided to prevent the judge addressing the meeting in Karachi. He was not allowed to leave the airport. His supporters in different parts of the city were assaulted. Almost fifty people were killed. After footage of the violence was screened on Aaj TV, the station was attacked by armed MQM volunteers, who shot at the building for six whole hours and set cars in the parking lot on fire.